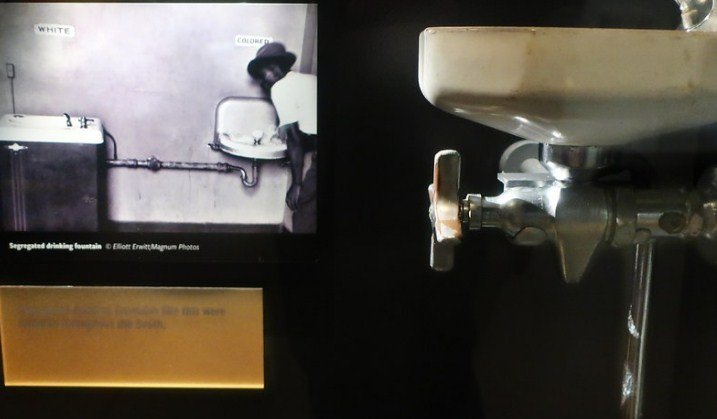

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 abolished the legal segregation of public facilities in the United States, but some remnants of the Jim Crow era still exist today. In some parts of the South, separate water fountains for Black and white people still stand as symbols of racial oppression and inequality.

The History of Separate Water Fountains

The practice of separating water fountains by race dates back to the late 19th century, when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the doctrine of “separate but equal” in Plessy v. Ferguson. This decision paved the way for the Jim Crow laws and customs that enforced racial segregation in virtually every aspect of life. Black and white people had to use different restrooms, schools, buses, trains, restaurants, hotels, theaters, and cemeteries. Drinking from the same water fountain was considered a violation of the social order and a threat to white supremacy.

Separate water fountains were not only a matter of convenience, but also of quality and hygiene. Often, the water fountains designated for Black people were poorly maintained, dirty, or broken. They were also located in less accessible or less desirable places, such as the back of a building or near a garbage can. The water fountains for white people, on the other hand, were usually clean, functional, and prominently displayed. The contrast between the two fountains was a clear message of racial hierarchy and discrimination.

The Impact of Separate Water Fountains

The experience of drinking from separate water fountains had a profound impact on the lives and identities of Black and white people in the South. For Black people, it was a constant reminder of their inferior status and their vulnerability to violence and humiliation. Many Black people avoided drinking from public water fountains altogether, preferring to bring their own water bottles or cups. Some Black people who dared to drink from the “white” fountain faced verbal abuse, physical assault, or even arrest.

For white people, separate water fountains reinforced their sense of privilege and superiority over Black people. They also served as a tool of social control and intimidation, discouraging any challenge to the racial status quo. Some white people who opposed segregation or supported civil rights were also ostracized or attacked for drinking from the “colored” fountain or sharing their water with Black people.

The Fate of Separate Water Fountains

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s challenged the legality and morality of segregation, and eventually led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This landmark legislation prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in public accommodations, education, employment, and voting. It also authorized the federal government to enforce the desegregation of public facilities, including water fountains.

However, the end of legal segregation did not mean the end of racial prejudice or inequality. Many white people resisted the integration of public spaces, and some even vandalized or destroyed the water fountains that were used by Black people. Some Black people also felt uncomfortable or unsafe drinking from the same water fountains as white people, fearing retaliation or contamination. As a result, many separate water fountains remained in use or in place long after the Civil Rights Act was enacted.

Today, most separate water fountains have been removed or replaced by modern drinking fountains that are accessible to everyone. However, some of them still exist as historical relics or monuments in some parts of the South. For example, in Ellisville, Mississippi, two water fountains that were once labeled “white” and “colored” still stand in front of the Jones County Courthouse. Although the labels have been covered up by plaques, the fountains still evoke painful memories for some Black residents who experienced segregation and discrimination. In 2020, the county held a referendum to decide whether to remove the fountains, but the majority of voters chose to keep them.

The Meaning of Separate Water Fountains

The separate water fountains that still stand in the South are more than just objects. They are symbols of a long, strange, and dehumanizing history of segregation that shaped the lives and identities of Black and white people. They are also reminders of the ongoing struggle for racial justice and equality in the United States. How people view and interpret these fountains reflects their attitudes and beliefs about race and racism, past and present.

Some people see the separate water fountains as part of their heritage and culture, and want to preserve them as historical artifacts or educational resources. They argue that removing the fountains would erase or deny the history of segregation and its impact on the South. They also claim that the fountains are no longer offensive or harmful, since they are no longer in use or labeled by race.

Other people see the separate water fountains as symbols of hate and oppression, and want to remove them or relocate them to museums or cemeteries. They argue that keeping the fountains in public places would glorify or normalize the history of segregation and its legacy of racism and violence. They also claim that the fountains are still offensive and harmful, since they trigger trauma and resentment among Black people and other marginalized groups.

The debate over the separate water fountains is not only about the fountains themselves, but also about the larger issues of racial reconciliation and social change. How can the South confront and heal from its history of segregation and discrimination? How can the South celebrate and honor its diversity and inclusion? How can the South move forward and create a more just and equitable society for all?

These are the questions that the separate water fountains still pose to the South and to the nation.

Comments